Today, the very same river is viewed simultaneously as a migration corridor for wild salmon, an emergency evacuation route for the residents of Lithuania’s capital, and a discharge channel for technogenic risks from Belarus’s nuclear program. These scenarios are incompatible, and choosing priorities is inevitable. The salmon in this story is not a metaphor but a strict biological indicator: if it disappears, the river will cease to be a living system, no matter how convenient it may appear to state strategists.

The Pre-Human Era: A Path Laid by a Glacier

For thousands of years, as soon as the glacier retreated, wild salmon moved upstream along the river that would later be named the Nemunas, in order to spawn in the upper reaches of its tributaries. The largest of these is the Neris, known further upstream as the Vilija.

Approximately ten thousand years ago, the geography of the Neris in the area of present-day Vilnius was different: the riverbed ran near “Ozas,” curved around the territory of the modern Compensa concert hall and the Park Town office complex, and merged with the Vilnia tributary slightly below the sakura park near the White Bridge.

Over time, the river changed its course. What remains of the former channel is known locally as the “Old Channel.” There is an urban legend attributing the change in the river’s course to Prince Jogaila, who allegedly wanted to bring water closer to the castle and Gediminas Tower. There is no historical evidence for this.

Most likely, the myth arose due to the artificial alteration of another river’s course—the Vilnia. It was indeed redirected between Gediminas Hill and the Hill of Three Crosses to protect the castle from the north. Before that, the river that gave the city its name flowed directly across what is now Cathedral Square, where the streets still follow its bends.

The Human Era: Dams and Barriers

In the Middle Ages, human impact was minimal, and for centuries salmon found their way upstream along the Neris and the Vilnia. A true catastrophe for the ecosystem unfolded during the era of industrialization. The growth of Soviet cities required enormous volumes of water and electricity.

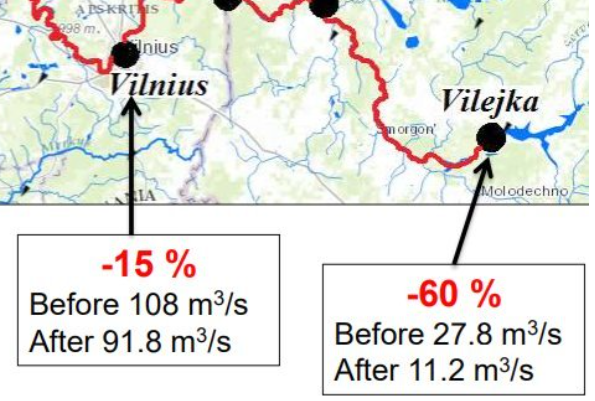

The upper reaches of the Neris–Vilija were blocked by the dam of the Vileika Reservoir to supply water to Minsk, and the Nemunas was dammed for hydropower. When these hydraulic structures were built, no fish passages were provided. The upper reaches of both rivers were closed to migration, and the fish population disappeared.

For Belarus, it was fortunate that the Neris flows into the Nemunas below the Kaunas dam—thanks to this, salmon spawning can still be observed in Vilnius and along the Belarusian stretch of the river.

The River That Unites: The Logistics of Smuggling

However, human economic activity on the river is not limited to hydropower. A paradoxical example of international “cooperation” is smuggling. While public attention is focused on balloons carrying illegal cargo, smugglers continue to use the water element, floating rafts loaded with cigarettes downstream.

One such raft entered history thanks to nature’s intervention: beavers that felled a tree into the river blocked the cargo’s path—long before the video of the “kurwa beaver” became an internet meme.

Thus, the river serves as an instrument of the shadow economy: Belarusians send “voluntary white death” downstream, while recipients in Lithuania are in no hurry to refuse it. According to studies, between 18% and 26% of cigarettes in Lithuania are of Belarusian origin, although officially they were not imported into the country.

The River That Divides: Borders of Worlds

Today, the border between Belarus and Lithuania is a watershed between peace and war. Cartographically, everything is clear, but in public consciousness disputes arise: where does the Belarusian Vilija end and the Lithuanian Neris begin? On social media, people joke that the Neris originates from Lake Narach (in Lithuanian, Narutis).

Geologically, this is not far from the truth: once, the lakes of the Narach group formed a single body of water, and the river was more full-flowing. Now, the Vilija stretches to the state border (and to that very tree felled by a beaver).

The Belarusian Threat: The Atom on the Riverbank

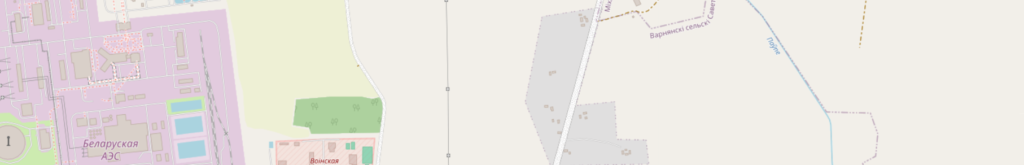

Just 30 kilometers from the Lithuanian border, a small tributary flows into the Vilija—the Polpa River (Paupa). This is a delayed-action ecological bomb. On the banks of the Polpa are located the Belarusian Nuclear Power Plant and pools for cooling spent nuclear fuel (SNF).

The first reactor of the Belarusian NPP was launched in 2021. Five years after the start of operation, spent fuel is to be unloaded into pools filled with water drawn from the river. In the event of a leak through the cooling system into the Vilija and drainage from the site into the Polpa, radionuclides would enter the Vilija, then the Neris, and then pass through the three largest cities of Lithuania—Vilnius, Kaunas, and Klaipėda.

Martin Lowe, organizer of the civic campaign “Stop the trains with nuclear waste” (United Kingdom), comments on the risks:

“Removing and transporting spent fuel rods creates numerous risks. It is important to remember that these rods remain extremely hot and radioactive for many years. Shipping them to Russia will increase Moscow’s plutonium reserves, and the risks of contamination during transport also affect Belarus. Given the extreme danger of movement, the prevailing approach today is that waste should be placed in dry on-site interim storage facilities.”

The history of the construction of the Belarusian NPP is rife with alarming incidents: the casing of the first reactor was dropped during installation, and the casing of the second struck a pole during transportation. The essence of the plant’s operation is as follows: uranium decays, releasing energy and turning into highly radioactive waste. After cooling in pools, the fuel is planned to be sent to Russia for plutonium extraction, and the residues will be returned to Belarus. The country will have to solve the task of burying this waste for centuries, avoiding a repetition of the scenarios of the 1957 Kyshtym disaster.

Belarus’s neighbor Lithuania also once narrowly avoided its own Chernobyl—in 1983, during the commissioning of the first unit of the Ignalina NPP, a problem was discovered in the design of the graphite moderator rods, the so-called “end effect.” Fortunately, no catastrophe occurred, because the design flaw was identified in time, described in documents, and recorded in IAEA reports. However, it was not taken into account at Chernobyl three years later.

Biologist Inessa Bolotina notes that even without accidents, the plant affects the ecosystem:

“Radiation affects fish in the same way it affects other organisms: immunity is weakened, and mortality of eggs and fry increases. An additional factor is thermal pollution. Salmonid spawning occurs in autumn, and low temperatures are necessary for egg survival. The discharge of warm water from the NPP can exacerbate negative climate changes.”

According to an expert who wished to remain anonymous for objective reasons, the original project envisaged discharging cooling waters directly into the river, where they were supposed to mix with the waters of the Vilija over a distance of 8–11 km.

“This is an enormous distance for a spawning river. We submitted objections, and during construction additional coolers were added—pools with fountains. So far, we do not observe a critical increase in water temperature.”

The Lithuanian Threat: Evacuation to Nowhere

Threats to the river do not come only from the east. The mayor of Vilnius, Valdas Benkunskas, fearing military aggression (the distance from the border to Vilnius Airport is only 28 km), stated that the city’s population could be evacuated via the Neris River.

At first glance, the idea seems logical: the river flows inland, away from the border. However, this plan raises questions, especially if one imagines a winter conflict scenario. But even in summer, the logistics look utopian.

The Neris flows westward at a speed of about 1 m/s. The distance from Gediminas Tower to Kaunas along the river is 174,000 meters. The drift would take 174,000 seconds, or 48 hours. Even if the process were accelerated, the journey would take almost a full day.

If each evacuee is allocated a minimum of 2 square meters on a vessel, evacuating 350,000 residents would require a flotilla stretching 30–40 kilometers. The fairway would not allow boats to be arranged wider than 20 meters. Questions arise to which there are no answers:

- Where would such a number of boats be stored?

- How long would the piers have to be for the simultaneous boarding of thousands of people?

- How can the rapid deployment of vessels be ensured under fire?

In addition, there is a hydrological risk. Belarus controls the gates of the Vileika Reservoir. According to Vilnius University associate professor Gintaras Valuškevičius, blocking the outflow through the dam would reduce the water level of the Neris in the Vilnius area by 15–25%. At a critical moment, the river could simply become shallow.

Dredging Versus Nature

In the context of evacuation and navigation, Lithuania’s Inland Waterways Directorate (Vidaus vandens kelių direkcija) proposes clearing the riverbed by removing six rapids. This would require extracting one million cubic meters of sediment and spending 20 million euros.

Lithuania’s scientific community has sharply criticized this project. The Neris is part of the protected Natura 2000 network, and large-scale dredging threatens the destruction of the ecosystem and EU sanctions.

An expert who wished to remain anonymous believes that salmon might adapt to the changes but hopes for civil society:

“In Lithuania, projects go through public hearings. People will ask uncomfortable questions, and I hope common sense will prevail.”

Why Is Salmon More Important Than Geopolitics?

It may seem cynical to care about fish when nuclear safety or war is at stake. However, inadequate plans—whether the construction of nuclear power plants or fantastical evacuation scenarios—only divert resources from real solutions.

Salmon is important for two fundamental reasons. First, the extinction of a species is irreversible. Inessa Bolotina reminds us:

“Wild salmon is a unique genetic bank. The farmed varieties we see in shops are created on its basis. Without the wild ancestor, this chain collapses.”

Second, wild salmon is the “canary in the mine.” Its well-being is a marker of the health of the entire river system. If it disappears, it means the environment becomes unsuitable for humans as well.

As noted by Karl-William Koch of the German group Unabhängige Grüne Linke:

“Protecting rivers becomes an inevitable issue for our own survival.”

The illustrations feature motifs borrowed from Belarusian, Lithuanian, Russian, and Norwegian artists, as well as photos from Google Maps.

If you are concerned about the fate of the salmon in the Neris River, the story of the Belarusian Nuclear Power Plant, or the destinies of all the other figures mentioned above, you can support our campaign here.